“Clowns aren’t made,” you tell your therapist inside her cream pristine office. “They’re born.”

She hums and taps her fancy fountain pen against the edges of her clipboard with your name at the top, where everything you’ve said, everything you are, has made it into ink-bleeding bullet points of flowery script.

“Care to elaborate on that?” your therapist asks, when her body language—politely intrigued—does not prompt a reply from you.

You pluck at the loose threads of your therapist’s couch. Look around her office at the portraits of animals and vegetal still lifes. Wonder how many of your neuroses and phobias live indelibly inside the pages of her clipboard, dissected and probed and analyzed. But there is one fear your therapist will never be able to understand.

For the first time since the session started, you lift your head to look your therapist directly in the eyes. And under them, a big, red nose bulges against her face—a nose only you know is there.

•••

You remember your birth. The white fluorescent lights, the clamoring doctors and nurses. Most of all, your mother’s screams.

Your mother, back when she still talked to you, before she gave you the therapist’s number and her credit card info and told you to figure your shit out or else, would say there’s no way for you to remember that delivery room tableaux. Infants do not retain their memories from birth. The initial awareness of the self develops gradually during early childhood, and never earlier.

But you do. You remember everything, and that is why your mother will never have the healthy relationship with you that she so craves.

You remember how her womb was like a torc around your head, squeezing you mercilessly. How the doctor’s hands were an incandescent brand on your brand-new skin. How the light hurt a lot more than the darkness ever could.

You remember looking around through a patina of lustrous blood and mucus glazed over your eyes. You thought that might be why everyone’s faces in the delivery room were so red and distorted.

Then, the nurses cleaned you of afterbirth quickly and efficiently before handing you back to your sweat-drenched mother. When your mother rubbed her nose against yours and said, little baby, welcome home, her nose bumped round and bulbous against yours. It ballooned and wobbled like a blistered sac of amniotic fluid. The color seared itself into your retinas. Red red red.

Even before the umbilical had been severed, you knew, despite being only moments old, that you and your mother would never again be connected.

•••

The truth is, everyone is a clown. You walk the street and witness people going about their day, powerwalking to work or taking their babies out on a stroll or meeting friends for an early brunch, and they all wear a red clown’s nose.

No, wear is the wrong word. You cannot wear something that can never be taken off. Everyone has a red nose but cannot see its redness or perhaps, you thought long ago, it was considered taboo to acknowledge it. Like some vestigial animal organ whose usefulness was too gauche to debate.

You used to wonder why clowns and their variations—the harlequin, the pierrot, the mime—ever made it to popular media. Were circus and carnival shows a society-approved way to externalize what everyone knew implicitly or instinctively? You still wonder, sometimes. But who do you even ask? Your mother is no help and neither is the therapist she’s paying to fix you.

In the street, a child picks his red, red nose, the nostrils flaring vilely with each twist. His mother scolds him, talks about all those germs.

You pause by a boutique’s window and study your washed-out reflection among the merchandise.

How your nose is small and strange and unred.

Perhaps that’s why the people around you ignore you, treat you as a separate entity from them and always have. Still, they wouldn’t be able to articulate why, like a blind spot in their perception, revealed to you, and you alone.

•••

“Is my nose looking alright to you?” you ask your first boyfriend.

He is ensconced in bed, distracted, glancing up from his phone. “Huh? No, it doesn’t look too big, no. Why, were you considering nose-slimming surgery?”

You touch your finger pads against the contours of your nose. Map out everything it is lacking. It’s no surprise that your boyfriend doesn’t see it, doesn’t see you. But at least your mother is talking to you again. She says therapy must be working for you to be making human connections at last. Several years after your peers, but better late than never.

Your boyfriend might be self-absorbed, but he is good for one thing. When you push away from your bedroom mirror and join him in bed, his hands slot magnetic around your naked waist. He slides further down the bed and lets you ride his face, his nose, fat and round as a plum, buried inside your core, straining your walls.

The sensation spasms both pleasure and revulsion down your throat, like another plum-sized organ has been wedged there.

And you know, as sensation crests and contorts your body, that you cannot keep walking through the world like that. So separate from the crowds, so fearful of your own reflection. Driving yourself mad with questions about what others have in excess, and what flesh of yours has always been inadequate.

Something has to be done.

•••

“You mentioned something, during our early sessions,” your therapist says.

Her clipboard and fountain pen for once remain positioned on the coffee table between you. This is your final therapy session, and you are graduating with honors.

“Mentioned what?” you ask, trying to gain time. Politely intrigued, you learned the body language from your therapist.

“‘Clowns aren’t made, they’re born.’ Do you still think that?”

You shake your head and say, “No, no, I don’t.”

Your therapist smiles. Brushes a finger against her red, red nose. You no longer care to speculate whether everyone else in the universe is in on some cosmic joke, your therapist included, except for you. The sessions, at least, have taught you that.

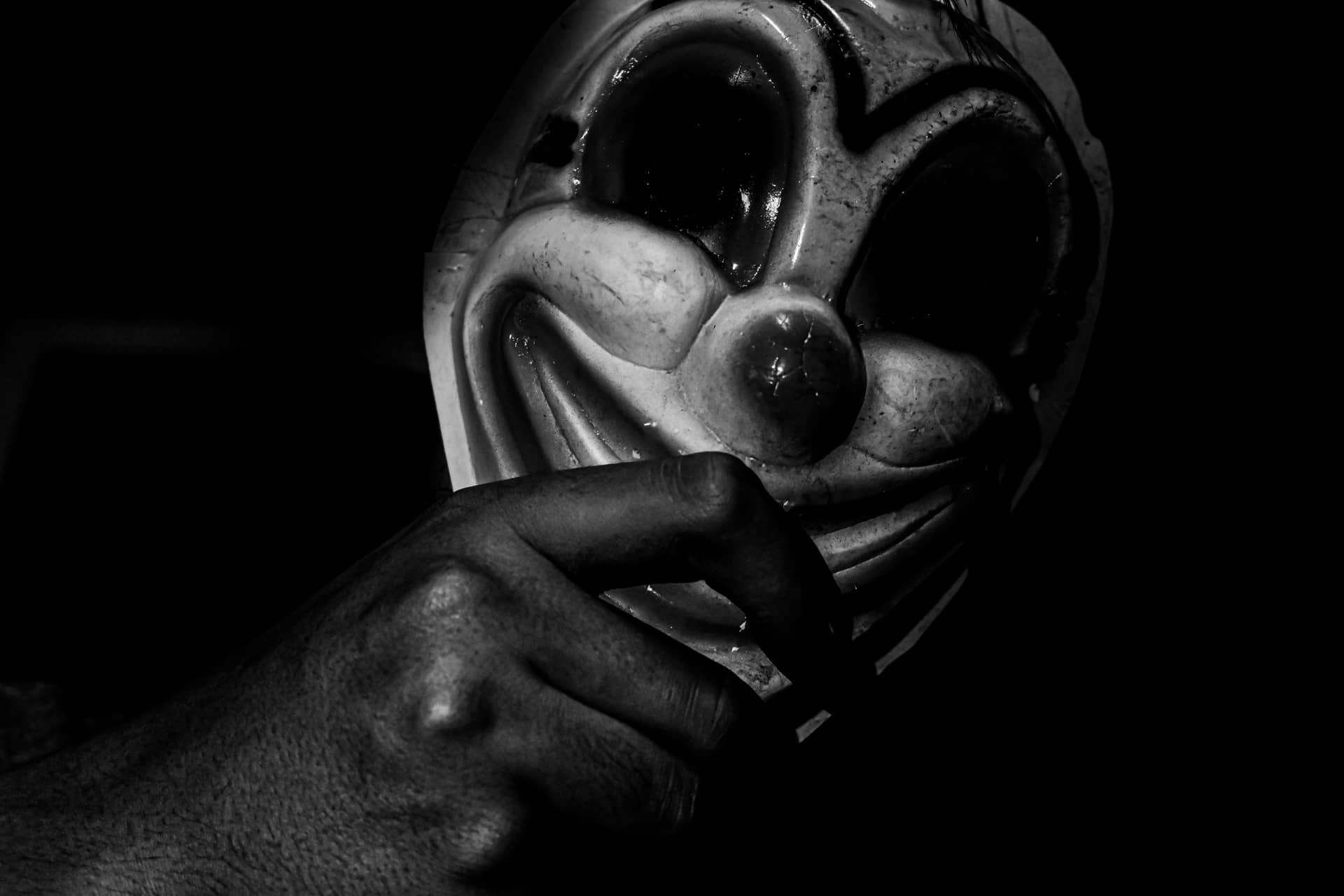

The knife in your shirt sleeve is hidden like a magic trick. You’ve been watching some circus videos, practicing through the voyeuristic projection of clown-ness. Concealed ace tricks and flowers squirting water, what a curious thing indeed.

But despite your slight-of-hand deception, you didn’t lie to your therapist.

You no longer think that clowns are born.

No, they are made. And perhaps this is what everyone around you already knows, has known all along. Why they couldn’t tell you about it—you must reach that conclusion on your own.

Your therapist’s big, red nose distends, like a fruit ready to be plucked.

The honed tip of your knife peeks out from your shirt sleeve.

You hope that, when you meet your mother later to celebrate the end of therapy, she will like your new nose matching hers.