Originally published in Shock Totem.

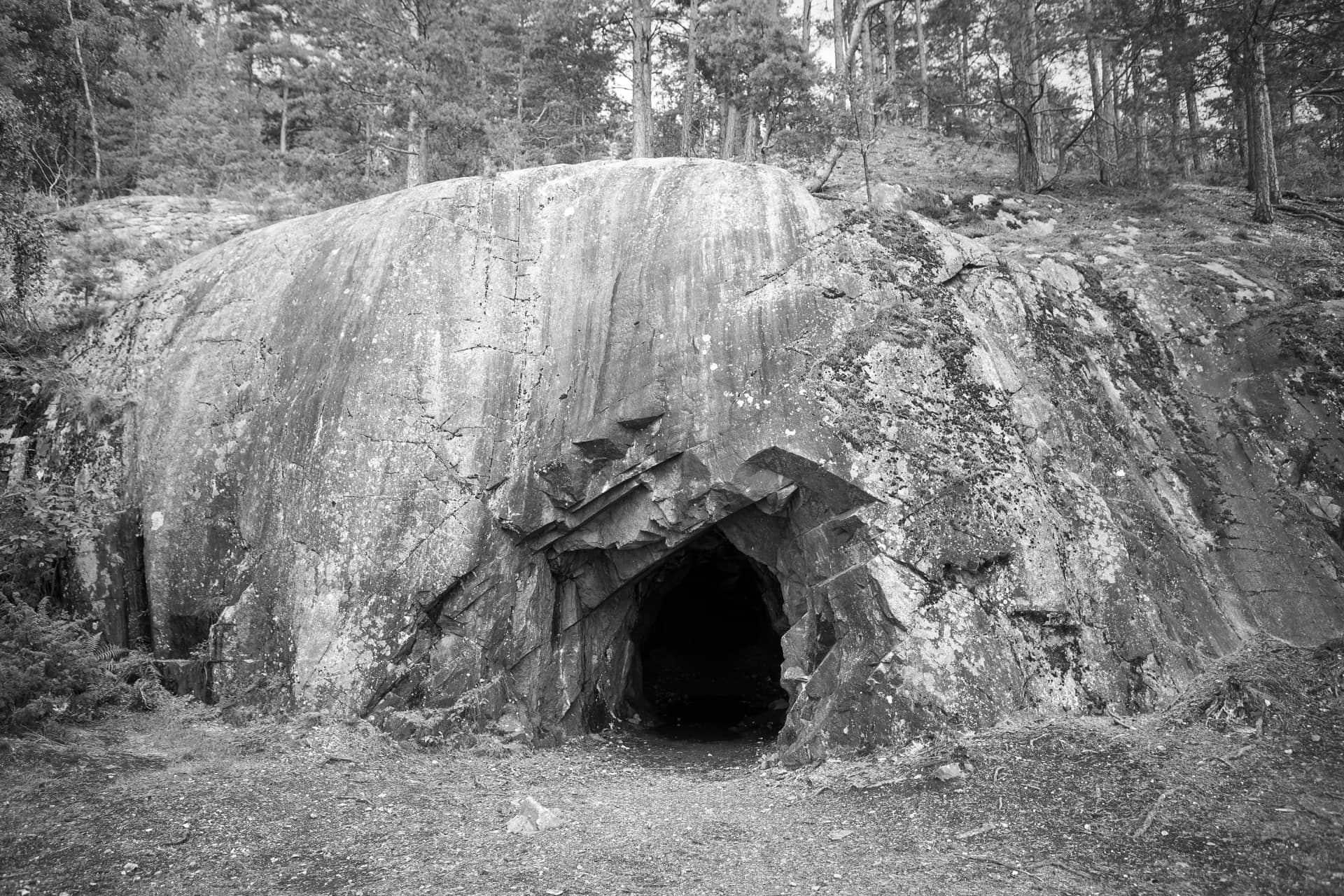

The darkness has teeth.

As children, we knew it. We were terrified of sleeping in our rooms alone. Afraid of the monsters that lived in our closets with toothy smiles that wrapped most of the way around their heads. Scared of the things that lived under our beds, knowing they would scrape their claws against our skin if our leg slipped out from under the covers. Our mothers and fathers reassured us that nothing lived in the dark that wasn’t in the light, but we knew this wasn’t true. As adults we park our cars under streetlights. We’re attracted to brightly lit neon signs. Pictures from space show that as soon as darkness spreads across the earth, the lights flick on. We’re still frightened.

When I was in college, my friend, whom I shall call Anne, and I studied mines for a geology project. Anne’s father was a miner, and one day we received special permission to don mining gear and follow him into the Earth for an hour.

“Darkness demands respect, girls,” he said. “Don’t move. Stay exactly where you are. Ready?”

We were ready. We weren’t afraid. We were strong, independent girls and the darkness wasn’t anything to be afraid of. I’d been telling myself this for years. After all, Anne’s father was there, his teeth shining white under his dark mustache. The rest of the team was there, as well. What could a little dark do?

We nodded. Anne’s father shouted something and the crew shouted something back. Then the lights went off.

The sheer power of the darkness made me suck in my breath. It was thick and heavy, weighty, like oil or mist. Every childhood fear I thought I’d outgrown came slithering back. Somebody shifted their footing and it echoed eerily throughout the unfamiliar mine. My eyes strained so hard for the tiniest source of light that they physically hurt. But there was nothing to see, just the absolute absence of light. Just the hunger and the possibilities. I reminded myself that I was an adult now, that this wasn’t real terror, that I only had to hold on for another five seconds. Four…three…two…one…

The lights came back on and suddenly I could breathe again. I turned away, lifted my mask, and discretely wiped at the corners of my eyes with my sleeve.

Anne’s father looked at us and laughed. He pointed and I realized that Anne and I had both grabbed each other’s gloved hands in the dark. We separated, feeling a little bit silly. But later that night, back in the safety of Anne’s room, she slammed down her pen.

“I was so scared,” she told me.

I nodded. “I am never, never going back in another mine.”

There was something I didn’t tell her, though. There was a reason why I was so heavily affected, why I stood there in the cold darkness begging for the lights to go on. It’s something that we don’t really talk about in my hometown.

I’m from a blue-collar desert town. There weren’t a lot of us, and we stuck together to overcome the harsh conditions. The town was basically divided into two main occupations—coal miners and power-plant workers. My daddy was a plant worker. His daddy was a plant worker. You went where the job were, and if the job left you out in the middle of nowhere, so be it. There weren’t many places more rural than my hometown. It still doesn’t have a traffic light. It was full of charm and dust and grit.

But when I was five, tragedy struck. There was a massive fire in the Wilberg Mine, and while one miner managed to escape, twenty-seven people were killed when their escape route was cut off. They were daddies, too. Granddaddies. Brothers. One of the victims was the first woman to die in a mine since women were allowed inside.

Twenty-seven people in such a small town meant that everybody was touched. We just shut down for a while after that. Friends couldn’t come over and play because we were being “respectful.” I couldn’t go to some of their houses because their mommies were still crying and couldn’t get out of bed. My mother baked cakes and loaves of fresh bread. She wrapped them up, put them in my red Radio Flyer, and we walked around town, dropping them off at certain houses. I remember thinking that homemade bread from a neighbor must be able to heal any wound. I was too young to know any better.

When I was about eight, I was walking downtown with an ice cream in my hand. I saw a friend curled up next to the mine memorial, crying. I offered her my ice cream, but I didn’t know what to say.

Years later she mentioned that she had nightmares of her Old Daddy showing up, his skin charred and cracked, just when she was hugging her New Daddy. She wasn’t betraying either of them; both were good, kind men who were wonderful fathers, but you can’t explain these feelings to a child.

That is what I thought about when Anne and I were in the mine together. That is why I swore I’d never step foot inside one again.

But Anne did. She started working in a mining control room. She fell in love with a man there and they were married. They worked together for several years.

“It isn’t as scary as it used to be,” she told me once. “Are you sure you wouldn’t like to come inside some day?”

“Never,” I told her. I was surprised at the venom in my voice. “Never, never, never!”

Then one August, her husband quit his job. I’m not exactly sure why. The very next day the mine collapsed.

My mother was the one who called with the news. I remember dropping the phone on the floor after she told me.

Anne’s husband’s team was inside. He wasn’t.

That day, sitting at home with his head in his hands, he’d said, “I should be in there. Those are my men. Those are my friends!”

Six miners were trapped. I knew every one of them or their families.

Even though I now live several states away, my soul is still tied to that town. The desert runs in my veins. What happens there deeply affects me. Those are my people. They are my lifeblood.

I know how dark a mine can be. The horror I had felt on that calm day in college, gripping Anne’s hand in the dark of the mine, her father beside us, was almost more than I could stand. That’s when we were without light for ten seconds. What would it be like to be trapped for days? To be crushed under the rubble? How did those brave men feel when they heard everything come down around them? If I thought of this, and I was only a friend, how did their families feel? What screamed through their minds when they turned their thoughts to their trapped loved ones?

Signs went up immediately after the collapse. “Pray For Our Miners.” “Don’t Give Up Hope.” “We Love You.” Children tied yellow ribbons to school fences. Friends, families, and reporters gathered at the site of the mine and in living rooms to monitor the desperate rescue efforts. Every little action was reported. I was glued to the news channel, riveted to the Internet, constantly on the phone. My heart hurt. My soul was in anguish. It brought up old wounds I thought were long—I hate to say the word—buried. But these wounds were suddenly ripped open. I wished I was five years old again, when I knew that the Big Bad had happened but I wasn’t fully cognitive of it. Grief is too heavy to handle as an adult.

It took three days to bore a hole into the mine. They lowered a microphone down, and everyone held their breath.

The silence was devastating.

What does this mean? we wondered. It meant, we told each other, that the miners retreated to a different part of the mine. It meant they were exhausted and conserving their energy. That’s all. It couldn’t possibly be anything else.

They took samples of the air and declared it livable. That’s what we focused on. We ignored the implications of that chilling silence.

More samples showed that the earlier conclusion was incorrect. The air was, in fact, fatal. The spine of the entire town seemed to bend and slump.

But we were not quitters. We didn’t just give up. The search rescue continued, although I think we all knew it had turned into a recovery mission. Still, nobody said it aloud. Not people from the town, anyway. The outsiders did that. Reporters. Family that flew in. People who didn’t understand that when things were at their darkest, you had to keep going. If you stopped, you fell—and if we fell at that point, I don’t know if we’d have been able to get back up.

Then there was a second collapse. Three of the rescue workers were killed and six more were injured. I still remember hearing the words, “The rescue has been called off.” I put my hands over my face and cried. We abandoned them. That’s how I felt. Although I realized that you can’t trade the lives of the living for the dead, we still left them to have their marrow sucked out by the dark.

I think Anne’s husband broke a little that day. He hadn’t been sleeping. He hadn’t been eating, or talking to anybody. He felt that he should have been in there with his team—but he was grateful he wasn’t. That, of course, made him feel worse. He didn’t want to hear things like “It’s all for the best” or “Trust in the Lord” or “Sometimes bad things happen to good people.” He didn’t want to hear that his reactions were normal and he would get through it. The term “survivor’s guilt” sounded small and patronizing to him. He was racked. He was screaming inside. He shut down. Hopelessness is unbearably heavy.

The “Pray For Our Miners” sign stayed up. It was ripped and faded by the wind, but nobody had the heart to pull it down. The relentless sun blanched the yellow ribbons into the color of bone. They were slowly untied, one by one.

Eventually they sealed the entrances to that part of the mine. The bodies of my friends are entombed there. I think about it when I drive by. Whenever I can, I try to take a different route to avoid it. It’s been many years and it’s still too raw.

Anne still works for the mine. So does her father. I hope her husband hasn’t gone back to work there, but sometimes there isn’t a choice in a small town. We lose and we mourn and we rail against our fate, and then all we can do is pick up our gear, take a deep breath, and head back into the waiting darkness.

And try to avoid its teeth.