(Originally published in Mannequin: Tales of Wood Made Flesh.)

First I feared them. Then I pitied them. Then I envied them.

Popular culture presents us with the “killer doll,” either as a supernatural hobgoblin or as a psychological delusion born from a ventriloquist’s psychotic split personality. As a child, fear of this demon—born of The Night Gallery’s Algernon Blackwood adaptation of “The Doll” and, later, “The Dummy” episode from The Twilight Zone—possessed and obsessed me. A childlike, uncanny thing moving with non-biological animation was, for me, the height of horror.

Case in point—“The Doll” of Night Gallery fame. I saw the episode at the age of four and had recurring nightmares about the Doll for the five years that followed. I can see her now, four decades and more later, perfectly rendered by my imagination. The Doll has a rather square face (like my own) with matted, blond hair and smeared black circles under her eyes. When about to kill, the lids pop open, revealing eyes that are blue and rather beautiful. Her closed mouth breaks into a fixed grin revealing bright, white teeth. The Doll sits up, and she seems to float towards me.

As per the Night Gallery episode plotline, the Doll “lived” only to exact revenge on a predetermined target. She was unstoppable once she had her prey in sight. She could be temporarily destroyed but would always return as good as new to complete her work. In my dreams, I was her sole target. I knew she had only to bite me once with her fatal venom to finish the job, as in the television episode, but she seemed content to extend my torment.

The Doll was more terrifying than any run-of-the-mill horror because of her unchangeable, static glee—baring her teeth and hunting me with a kind of mechanical joy. The Doll never made a sound, and often I couldn’t actually see her during my nightmares. But even hidden, I could feel her presence focused like a magnifying glass on my dream self. I might be sneaking in a dreamscape version of my own kitchen and turn to see that a small portrait of a stylized cat was now the hungry visage of the Doll.

In the Doll’s unwavering glass eyes and manic, fixed grin, I imagined this empty vessel wanted nothing more than to absorb everything I was or would be into its vacancy. Its clockwork consciousness. Automatonophobia, for me, was simple fear of my identity collapsing and becoming that automaton, that nothing.

Many nights I would awaken screaming after a doll dream, unsure whether I was awake or not. The Doll’s small, square face might appear just over the foot of my bed or her distinctive form might surprise me in the dark hallway on my way to the bathroom. On countless nights I begged celestial forces to protect me. My one and only prayer was a simple one—don’t let me dream of her tonight.

•••

Meanwhile, still a young boy, I began witnessing all too real, waking nightmares—one family dog after another struck and killed by vehicles on the suburban street where we lived. After the first canine death—a beautiful, young sheltie named Sunny—I begged my parents to put up a fence around our house. They refused but continued taking in dogs. And I witnessed all their subsequent, violent deaths. In the years that followed, I tried to keep our animals indoors, but at some point, I always slipped up.

The last death I remember witnessing was that of a female mutt-puppy named Pepper. By then, I was determined to ignore the doomed animals. But Pepper was an especially intelligent and kind animal, and her charms wore me down. I recall one morning my resolve gave way, and I realized all at once that I loved her. The very same day, she slipped through my legs as I opened the front door to get the mail. It is one of my most vivid and painful memories. Pepper slips out. I am yelling her name, running towards her. A car zooms around the far corner down the block. The driver, a teenage boy, sees Pepper toddling across the street. The boy smiles, speeds up, swerves towards Pepper. The impact. My hysterics as the boy pulls over, exits the car with a snickering friend, rings our doorbell. Through my sobbing, I am aware of my mother opening the door.

“Hey lady, is this your dog?”

“Yes. Would you help me move her body into the backyard?”

“Some people would do that,” the boy replies. Shrugging, he turns his back on my mother and gets back into his car.

The boy and his friend smirk at me, weeping over Pepper’s body. The car starts to move again. I chase after it, screaming, holding the small, broken figure in my hands.

I don’t remember how many of these traumatic canine deaths I witnessed, but I remember the bodies—once energetic and glowing with life, in a moment transformed into twitching and, finally, still forms. I see their bright, reflective eyes—so like The Doll’s eyes, staring through and beyond me.

And, all the while, the Doll nightmares continued. One night, she was chasing me as usual through a dream version of my attic. All at once, I realized that I was dreaming. Then something unprecedented happened. First, I stopped running and turned on the Doll. Her wicked grin faded into a grimace of doubt. The dream’s POV shifted from first to third person. I could see my face, now with a bloodthirsty, fixed grin. I stooped down and grabbed the Doll by one of her tiny, filthy legs, and ripped her limb from limb. To defeat the Doll, I became the Doll.

I awoke from the lucid dream, giggling with relief and joy, and for a few days I thought I was free from further nightmares. But then I happened to watch “The Dummy” episode of The Twilight Zone, and I realized my automatonophobia was not quite extinguished.

As a child, none of the mannequin-brethren frightened me more than ventriloquist dummies. As I would realize many years later looking at my own three-year-old daughter, ventriloquist dummies are similar in shape and size to human children. They appear alive via the ventriloquist’s movements and thrown voice. And when these wooden and plaster child-replicas are “active” in such a way, a willing audience more or less believes in their reality. But it is not the dummy’s uncanny movements that are, by themselves, frightening to some of us. It is when the dummy is inert—perhaps sitting on a chair by itself after the show is over—that the real shivers begin. Because we’ve seen them move and appear to talk on stage, we know those staring, vacant dummy eyes can move back and forth. We know that still dummy head can swivel. We know that closed dummy mouth can open. We know that silent dummy can talk. What’s more, we now expect to see these signs of life even when the ventriloquist is absent. Sit and stare at a dummy in an otherwise empty room, and you’ll see what I mean. Sit and stare at the dead body of a loved one (a dog or a human being), and you’ll feel that same expectancy.

•••

I became a ventriloquist when I was nine years old to stare down my burgeoning dummy fear. refusing to endure more recurring nightmares with a ventriloquist dummy in the Doll’s place. That Christmas, I asked my parents for a twenty-five-dollar Mortimer Snerd knockoff. I read the enclosed, three-page pamphlet on the basics of ventriloquism and took to the craft easily. After acclimating to a dummy in my house (and a setback thanks to my cruel and imaginative older brother’s shenanigans), my fear abated. I became good at ventriloquism. Then I became excellent at it, performing on stage, booking birthday parties and the like. Three years later, I received a loan from the bank and purchased a custom, professional-grade ventriloquist dummy, which I dubbed Reggie McRascal. He had (and has) real human hair, large, blue eyes that wink and blink, a 360 degree swiveling head and (human hair) eyebrows, which move up and down. Aside from darker skin color and a snub nose, in fact, he looks like me.

By that time, my fear of dummies, dolls, and the whole hollow-headed crew had faded away. In fact, I felt a growing affection and pity for my Reggie. I felt guilty when I left him in his case for too long or when I didn’t practice with him long enough. He seemed lonely for attention, as if every second in the darkness of the case was a conscious torment. When I was a teenager, the dummy and I began having long conversations, which burbled up from my ventriloquist practice sessions. Reggie had become a friend—a more aggressive, funny, angry and spontaneous version of myself. Fearless—able to say the most awful and hilarious things.

My almost-adult mind knew the dummy was empty, devoid of any kind of consciousness. And yet…all those hours staring at myself and him in the mirror imbued Reggie with a kind of phantom personality. I began to imagine I knew what he was thinking, even when he was sitting across the room from me. His painted smirk became knowing, sarcastic. Far from him wanting to absorb me into an uncanny emptiness, it was as if I had filled his hollow form with a kind of unwanted humanity. A human personality. He glowed with it and became ironically larger than life (at least in comparison to my own shy, nascent personality). When I was practicing or performing with Reggie, I expected him to move, to talk, with or even without my unconscious help. This idea was neither uncanny nor monstrous to me. It was normal.

•••

One night when I was seventeen, though, a practice session in the mirror went awry. Reggie interrupted our skit to scold me at length for my lackluster romantic life—specifically, my lack of initiative in asking out a girl I liked. We argued. The dummy made me cry. I had no idea what Reggie was about to say. I cast him down on my bed. Hours had passed, I realized, since the conversation began. I put Reggie back in his case—at the time I thought for good—because I was no longer afraid of the dummy. I was afraid of the human relationship I had formed with what I knew was an inanimate object but felt was another human being.

College years brought the death of all my grandparents but one and a big move to another city. I did not take Reggie with me. The years that followed had little to nothing to do with dummies. Reggie became a bizarre footnote in my life, an oddity to pull out for friends and family on rare occasions when the spirit moved me. Of course, I was careful to put him up shortly after taking him out, lest Reggie began speaking again of his own accord.

In the meantime, my attitude toward all automata changed. Long gone were the days when I couldn’t bring myself to sit alone in the room with a creepy, big-eyed, staring doll. On the contrary, I started to develop a deep feeling of connection to and affection for all hollow-headed figures. I couldn’t have said why at the time.

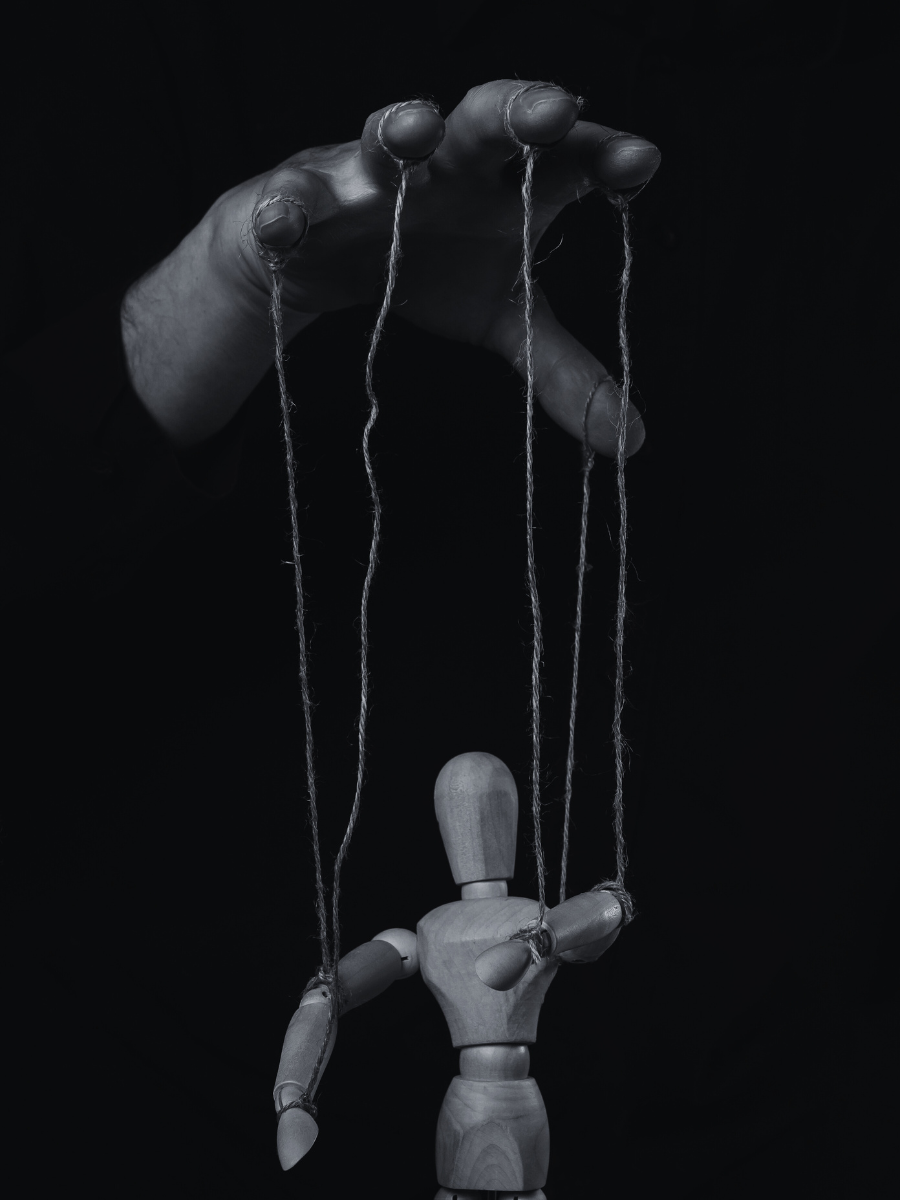

I had my first bout of significant depression as a young adult. With college done, it was as if the future that faced me folded into itself. I had long known extinction was the destiny of all living things, but now I felt that black hole of mortality pulling me towards it. I moved into a small apartment and brought Reggie with me, now out of his case, sitting on a chair in my tiny living room. I never practiced with the dummy anymore—too despondent to attempt such a thing—but I could no longer bear to leave him locked up in a suitcase. I identified with him and his mannequin-brethren more than ever. Like them, I was subject to forces beyond my control, helpless in an unknowable universe.

I swung back and forth between the poles of despair and panic in nauseating, wide arcs. The utter stillness of the apartment each late night when I tried to sleep plagued me with an unwanted flood of compulsive thoughts. I started hearing a steady clacking from the living room outside the open bedroom door. It was the unmistakable hollow sound of a dummy’s plaster mouth opening and snapping shut in the darkness. I remember dreading that he was moving out there by himself. I remember hoping he somehow was.

As the days turned to weeks and months, the world around me began emptying out. I left the apartment only to fetch junk food and to work, which I did in an automated fashion. My coworkers had become puppets, pulled this way and that by supervisors or their own senseless compulsions. This perspective was not limited to others. Every time I looked in a mirror, I saw a panicked, wide-eyed dummy staring back at me.

Meanwhile, I had long ago stopped cleaning up after myself. Dishes were piled high and foul, never to be washed again. Trash was rarely taken out and accumulated in grocery bags in the kitchen and living room. Soda bottles littered the filthy wall to wall carpeting. The bathtub looked and smelled like a swamp. Soon, the whole apartment resembled one. The apartment attracted a terrible ant infestation, which I allowed to prosper—sometimes spending late afternoons after work watching the lines of the tiny automatons marching along, programmed to obey but never understand.

Every night I heard the hollow-headed clacking from the living room. Open pause pause clack. Open pause pause clack. And now, night or day, whenever I closed my eyes, I envisioned rapid-fire images of self-violence. A bullet exploding out of my skull, spewing brain matter on the apartment wall. A steak knife plunging into my stomach, ruined intestines and bloody shit squirming out. Fingernails wrenched off one by one with needle-nose pliers.

Understand, I didn’t want to do harm to myself—let alone kill myself. These terrifying images were my new waking nightmares, and my existence had been drained of all lucidity.

Now when I looked in the mirror, I saw a dummy in an aspect of despair and terror. But I saw a glint of something more—the staring eyes of my long-lost dogs, Sunny and Pepper and the rest, staring through and beyond me.

I spent a lot of time sitting in the living room when I returned from my work at the library, staring at Reggie’s inert form. The sight of a motionless ventriloquist dummy may drive someone insane if they stare at it long enough, just as staring too long at a corpse might. We are afraid (hope) that both dummy and corpse will move again. And this fear (desire) might make us wonder whether our own animation (both physical and mental) is as artificial as the dummy’s.

I stopped paying all my bills. The power company and credit card collection services inundated me with angry letters and phone calls. Then my phone was disconnected.

One evening, soon after discovering an eviction notice on my door, I tried to move the dummy’s eyes with my mind. I sat across from him in the semi-darkness, and—after at least an hour of mesmerized staring—Reggie’s eyes shifted to the left. I screamed and fell and got up, stumbling backwards into my filmy living room glass door and out of it onto my tiny balcony. Hyperventilating. Afraid to enter the black rectangle of the door. Afraid of what I had done to Reggie. Afraid of what had happened to my mind.

•••

I sought and received help via psychiatric drugs and psychotherapy shortly thereafter. Both depression and panic and delusions subsided with time. I moved, of course (sans security deposit and with a nasty stain on my credit record). But my year alone with Reggie in that terrible, quiet, disgusting apartment changed my relationship to the dummy and its mannequin-brethren. My complicated fear and naïve pity of them morphed into nostalgia and real empathy. A true kinship.

Following my mental breakdown, I spent the better part of the next twenty years working out a simple question. What it is about dolls, dummies, puppets, and mannequins that unnerves and fascinates some of us?

What I have discovered is this: these anthropomorphic, hollow-headed bugaboos are simply too much like us, both alive and dead. Some years ago, I was diagnosed with a cerebral aneurysm. It unmoored me from my “life’s story” and forced me to stare into that impossible vacancy beyond my own death. Isn’t that both the struggle and paradox of our collective existence as sentient organisms? Aren’t we all terrified and fascinated to one degree or another by our own inevitable dummyhood? We eventually will be just as motionless—just as empty—as they are.

But, unlike us, our mannequin-brethren never suffer. There is no middle ground of consciousness between poles of blank forever. Consider the dummy, sans ventriloquist, sitting there by itself in an ideal state of meditative emptiness—neither alive nor dead.

And this brings me to the feeling I have now whenever I pull the dummy out of its case.

I envy the dummy. I admire it.

Why? It has not aged. All that time in its case, all those years, have meant protection from the elements, from time itself. Any flaw—a bit of rubbed off paint on the neck from plastic neck hole friction for instance—can be easily mended. Not even dust has been allowed to collect on the dummy. Next to any biological organism, it is ageless. As humans, we are not so lucky. The skeleton-dummies inside us wear down and become brittle with the years. The joints become painful and worn until they are unusable. The skin that covers them becomes sagging, wrinkled and papery thin—quick to tear. Our movement slows until we are inert and then utterly still things. Our brains shrink and malfunction and stop. Our hearts tire and sicken and stop. This degeneration and ultimate failure is inherent to our beings. Is it any wonder that our ancestor’s worshiped idols, which have a semi-permanence our own bodies and minds lack?

And that leads me back to where I started all those years ago as a child running away from the Doll in the endless hallways of my nightmares. I haven’t had a dream about her since I was nine years old. But if—as the elderly man I may become—I could turn around upon the Doll, I wouldn’t set a toothy grin upon my face and rip her limb from limb, as I once did. No. I would surrender to her. I would sit down, draw her into my arms and let the greedy void inside that tiny body consume anything that might remain of my human identity. My life story.

Yes, I envy the Doll and her mannequin-brethren. They look like us, yet they are more serene than we can ever hope to be.

As living beings, I used to imagine that Reggie had a personality. I realize now that it was all me—the illness that is my own consciousness, my perceived separateness from the inanimate past and future projected into a hollow piece of wood, plaster and paint made to resemble a human being. I am the one still possessed with the unrelenting idea that I am a person. But Reggie has never shared this ailment. I—not the dummy—am the one who fights back the rapid-fire, compulsive memories and future-projections that ricochet throughout my mind every waking moment of every day.

The dummy is the answer. The dummy is my future.

The dummy is your future.

When I take Reggie out of its dusty, old case these days and perform, usually for my daughter or an audience of one in the mirror, the dummy’s manner couldn’t be more different than it was those many years ago. The dummy is physically unchanged, but the words I throw into it have become shy, childlike, kind, nascent. It is neither aggressive nor angry anymore. There is peace between us now, for I know the dummy sees me – the real me.

I recognize myself in the bright, reflecting nothingness of its eyes.