Until the day she died, George Forster’s wife wanted to live with him. Instead, she lived with her mother; George rented a room in a boarding house. Of their four children, one had died, one was a babe in arms, and two lived in a work house. You know the sort of place—Dickens would later describe it. Husband and wife spent their weekends together. George worked for a London coach-maker and was said to be a good hand, but there seems never to have been enough money for a family household, no matter how hard Mrs. Forster pressed the matter. A clue to the reason why comes out in the testimony at George’s murder trial. Both versions—his own and the Crown’s—show him and his wife carrying the baby on a round of pubs, drinking porter and rum.

The crisis—the public part of it, anyway—came on a Monday morning when a canal worker found the body of a baby bumping up against his boat. The worker was dispatched to drag Paddington Canal for more. Three days’ diligence rewarded his efforts with the body of Mrs. Forster, which had tangled in some underwater growth.

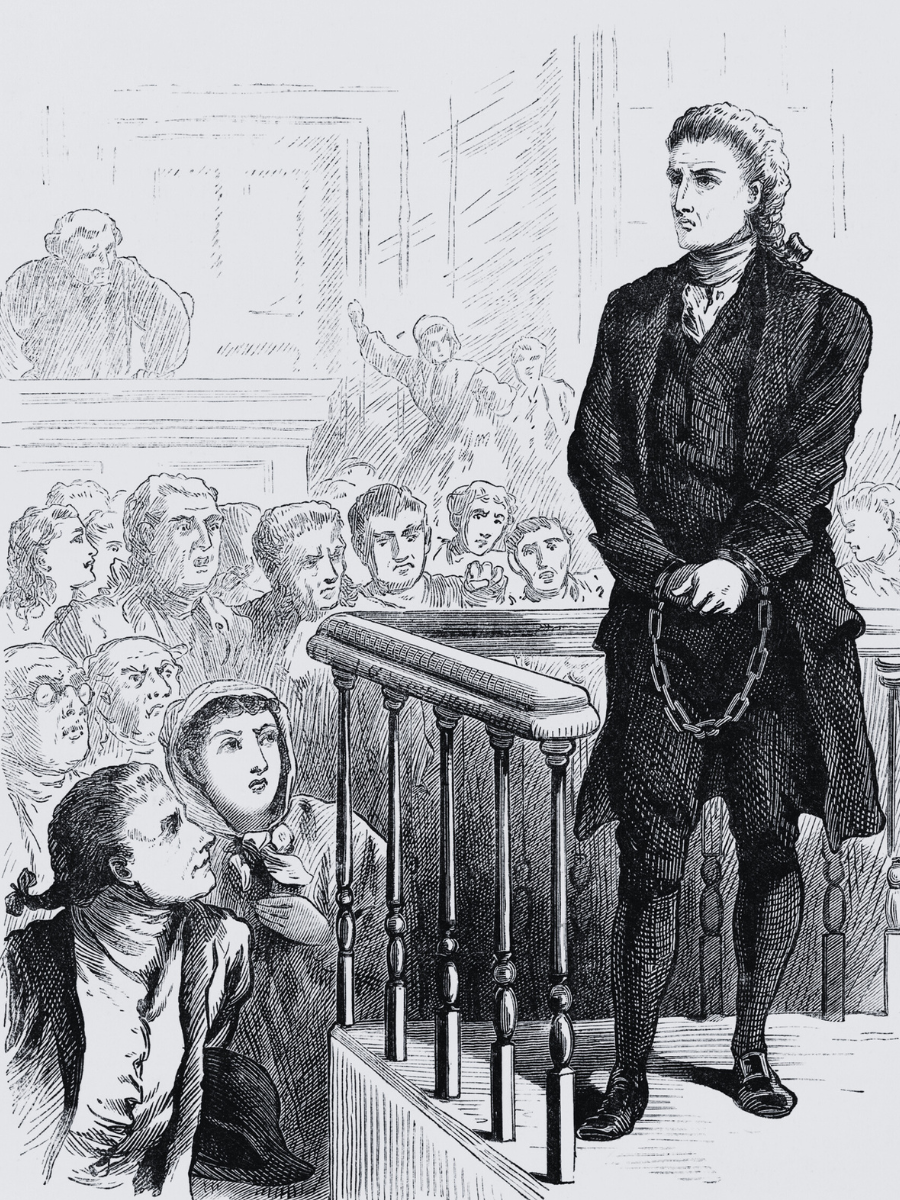

At the trial George Forster protested his innocence. The jury, however, were swayed by certain inconsistencies in his timeline, and by the improbability of his alibi. He said he’d spent much of the day walking to the workhouse to see his other children, but had turned back without doing so when he realized how dark it was getting.

He was sentenced to hang and then be dissected. In those days, long before it was fashionable to donate one’s organs, bodies for medical experimentation and training were hard to come by. It was a powerful taboo. Some Christians expected to stand up bodily when Jesus returned in triumph. Resurrection required a body more or less intact. It seems absurd, in light of today’s science (not to mention today’s zombie movies), to take that necessity literally, but many did. Forster’s sentence, therefore, was harsher than death. It ensured he would not have an afterlife. At least, not the good kind.

But everlasting damnation was not the worst of Forster’s worries. He’d heard of people waking up during dissection. There were, in those days, no EKGs, nor even the concept of brain death. Forster’s case, in fact, was to become one of the first steps toward such an electrical definition of life. No, the practical method of making sure there had been no misdiagnosis of death was for family to sit up with the corpse until signs of decay set in. Forster would not be granted such an interval.

While awaiting his execution date in Newgate Prison, he fashioned a knife and tried to gut himself. To his annoyance, he survived.

There was one way left. He’d need the help of friends at the gallows.

On January 18, 1803, having allegedly confessed to the murders, the twenty-six-year-old Forster was led up the scaffold stairs. The prison chaplain briefly prayed with him. A hood was slipped over his head. The trapdoor clattered open.

And this is when Forster’s friends sprang into action. They rushed forward—not to save his life, but to make sure he lost it. They seized his feet and pulled.

Possibly this effort didn’t succeed in snapping Forster’s spine, for the researcher who would soon work on his corpse found his lungs deflated and the large blood vessels in his head distended—signs of asphyxia. Perhaps the friends had helped hasten that. In any event, he left the gallows most sincerely dead.

The researcher, one Giovanni Aldini, could now begin his work. He wasn’t the usual anatomist or medical school professor. What he proposed to do was shocking. It’s going to remind you of Frankenstein; indeed, Forster’s experience is thought to have been among Mary Shelley’s inspirations. Electricity was Aldini’s game. Researchers had worked at understanding it for decades. They were fifty years past the point when Benjamin Franklin and other kite-flying experimenters had proved lightning a form of electricity. They were thirty years past the point when Aldini’s uncle, Professor Luigi Galvani of the University of Bologna, had discovered you could make dissected frogs twitch by touching them with scissors during a thunderstorm. Lately they had found that electricity could decompose water, which had seemed fundamental, into constituent gases.

The electric explanation of life fascinated Aldini—and educated people generally. Creative experiments abounded. If life was electric, might not an extra dose prove medicinal? Patients had already been treated with electric current for constipation, rheumatism, and insanity. (Despite dubious results, shock remains a psychiatric treatment today.)

With dead bodies, things had already progressed far beyond frogs. For instance, a scientist named Weinhold had beheaded kittens, then extracted their spines and replaced them with batteries made of zinc and silver plates. The carcasses sprang into action. Weinhold interpreted certain of their motions as gamboling play. They fell inert within minutes, but Weinhold felt encouraged to speak of resurrection as a real possibility. Aldini and others had coaxed motion from the bodies of decapitated criminals—and from their heads. The promise of human resurrection was in the air.

Man-made resurrection was a scandalous idea. Science had long followed theology in the belief that human beings were motivated by souls. Souls were gifts from God. It therefore followed that only a divine hand could restore the soul to a body. One of the miracles that proved Jesus’s pedigree was raising Lazarus from the dead. Another was His own return from the tomb. These events were mere foreshadowing for the raising of all the faithful in the end times, excluding people with ruined bodies like George Forster. But if men with metal plates and saltwater could resurrect the dead, it meant Christianity itself was in doubt. Or maybe it only meant that, like some modern Prometheus, you could put the tools of the gods into human hands.

Aldini, however, was not much interested in theology. He was a doctor; his interest was saving lives. In particular, he wanted to know if galvanism could restore people deprived of air in accidents, such as drownings and cave-ins. These people were said to be in “suspended animation.” Some of them had been roused by forcing them to smell ammonia, by injecting air into their lungs, or even by bleeding them with lancet or leeches. Aldini (who only later learned of the leg-pulling rabble and the possibility that Forster’s spine was broken) hoped Forster’s strangled corpse would replicate the condition of those who died by accidental suffocation.

There was, incidentally, a precedent for reviving an executed man. More than 30 years before, a street criminal named Patrick Redmond had been hanged, seemingly to death, and then revived by an incision that let air into his bronchial passages. But that had happened long before galvanism made headless men move, and was now mostly forgotten. The spectators gathered this day were ready to see larger significance in what Aldini did to the corpse of George Forster.

For his first experiment, Aldini wetted Forster’s ear with saltwater (a good conductor). He then connected his batteries—primitive affairs made of zinc and copper plates immersed in water—to Forster’s head—one electrode to the ear, the other to the mouth. Forster’s jaw quivered. The nearby muscles moved.

The left eye popped open.

There were gasps. Some spectators rushed for the door.

Then, Aldini applied an electrode to each ear. Forster nodded. His entire face convulsed. His lips and eyelids twitched. Aldini held one electrode steady and moved the other to the nose. The motions increased.

Again, Aldini held one electrode to the ear. He moved the other to the sensitive, nerve-rich rectum. The entire body reacted, so as “almost to give an appearance of re-animation,” as Aldini put it.

Next, Aldini compared the effects of galvanism and a “volatile alkali.” The latter term refers to several forms of ammonia. This is the stuff that had already saved the lives of a few drowning victims. You apply the sharp-smelling substance to the lips and nostrils. It evaporates rapidly, irritating the mucous membranes and, in the best cases, provoking the body into gasping for air. Breathing resumes. Mixed with more agreeable scents, the volatile alkalis were in use as “smelling salts” well into the 20th century. Aldini found that a volatile alkali by itself had no effect on Forster, but combined with the galvanic current, it produced a strong reaction, more than he’d achieved with the current alone. The convulsions engulfed not only the head, but also the deltoid muscle of a shoulder. He later speculated that, if not for Forster’s spine-snapping friends, the combination might have restored him.

Now it was time for the expert anatomists who assisted Aldini to take a hand. Aldini wanted to test galvanism on certain interior structures. The anatomists obliged him by dissecting to expose them—the nerves of the wrist, the muscles of the thumb, the biceps. In all these sites the current provoked admirable responses, including a stiff jab that looked as if Forster were fighting off the doctors. (Other scientists had caused a corpse to lift 50 pounds.) Aldini again compared other stimulants to galvanism. Forster’s biceps did not react to being stabbed with a scalpel, swabbed with a strong alkaline, or burned with sulfuric acid. Only electricity moved this muscle.

On to the heart. Aldini applied the current to its various parts—its surface, the muscle fibers, the coarse ridges inside the ventricles. Those big southern chambers remained flaccid. Only an upper chamber, the right atrium, could be coaxed into significant motion. This result was not entirely unexpected. Other researchers had already found that voluntary muscles, like the ones in the arms and legs, behaved differently under the probe than involuntary muscles like the intestines and heart. For the involuntary functions, it was best to stimulate the nerves instead of the muscles. Even better—implant a chunk of metal in the spine and wire it to the heart. Or inject warm saline into the aorta to mimic flowing blood. Hearts were reluctant to beat again, but once set in motion, they tended to keep going even after the current was removed. The window for restarting a heart was brief, however—much briefer than for other muscles. Perhaps that window had closed for Forster before Aldini’s team even cracked his chest.

In any event, implants and such were not on Aldini’s itinerary with Forster. The doctor did, however, ply his electrode on the spine, the bulging muscle of the calf, and the buttocks, all of which continued the disappointing trend. The sciatic nerve that supplies the thigh took no interest in the electric stimulation, but the thigh muscles themselves were far more responsive. There was a gratifying kick.

Seven and a half hours after the hanging, with parts of George Forster’s body apparently game for more, Aldini’s primitive batteries gave up.

The experience jolted the spectators, emotionally speaking. Some thought they’d seen a resurrection. One of them, a Mr. Pass, who worked as a custodian at the medical college, never recovered his composure. He died within hours. To date, he has not risen.